Why is Steve Bannon so determined to find an ‘Irish Trump’?

There has been a heated reaction to former Trump adviser Steve Bannon’s recent statements about fomenting a right-wing putsch in Ireland and creating an “Irish Trump”. But perhaps more interesting than his ambition is how Bannon’s views have been shaped by his Irish-American background – and what they tell us about the state of Irish America today.

Bannon has a larger-than-life biography, reinventing himself in Gatsby-like fashion – from naval officer to investment banker to Hollywood film producer to news media executive to Maga architect. But there is only rarely mention of his Irish-American roots. Like Jay Gatsby, he has elided his impoverished ethnic origins, while advancing what his former colleague Ben Shapiro called his “aggressive self-promotion” and “unending ambition”.

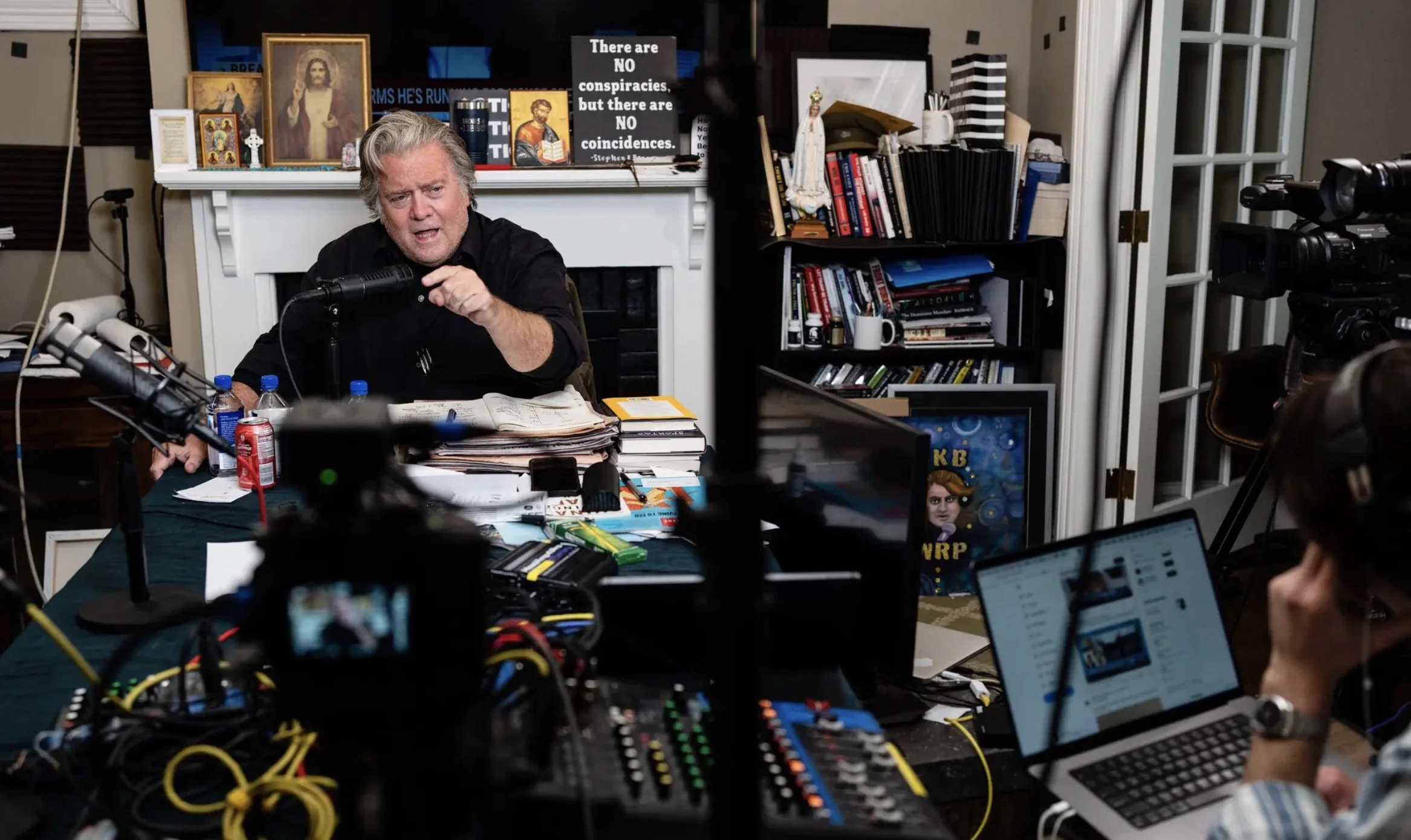

An Irish version of Bannon’s bio might start with his ancestors who arrived from Cork in the mid-20th century. It would certainly cover his experiences growing up in an Irish American-family in Norfolk, Virginia, and attending a Catholic military high school in Richmond. That admixture of Catholicism and militarism echoes into the present and his advocacy of “spiritual warfare” - spot the Sacred Heart picture in the “War Room” in the above image.

For some extra colour, an Irish bio might relate the story of his brief marriage to his third wife, a former Rose of Tralee contestant from Limerick who admitted smuggling phones and drugs to her boyfriend in a Miami jail, struggled with addiction herself and was banned for life from Aer Lingus for air rage.

More mundane but perhaps more telling is Bannon’s self-description, during an interview with Bloomberg News in 2015, when he remarked: “I came from a blue-collar, Irish Catholic, pro-Kennedy, pro-union family of Democrats.” The comment is significant, as Bannon was emerging into public consciousness as a key Trump adviser and knowingly positions himself as emblematic of a rightward journey in Irish America over the past 60 years.

Alt-Irish

For much of the 19th and the first half of the 20th centuries, Irish identity in the US evolved around the urban immigration experience, ethnic nationalism, Catholicism and political investment in the Democratic Party. By the mid-20th century, the cultural glue of this ethnic community came apart as Irish-Americans became middle-class suburbanites and appeared to assimilate into the white American mainstream.

Amid the national discord of the 1960s and 1970s, which saw the unravelling of the New Deal coalition and sociopolitical upheavals surrounding race and civil rights, the ethnic strings tying Irish Americans to the Democratic Party were broken. Many Irish moved rightward.

The seismic political realignments of that period not only reshaped Irish American political culture and identities, they echo into the present, where they inflame the culture wars around abortion, immigration and much more. Irish-American voices from Pat Buchanan to Bill O’Reilly to Bannon himself have championed a populist politics of white grievance and anti-immigrant nativism.

The prominence of what has been termed the “alt-Irish” among right wing and white nationalist sectors of American politics and media has lent the culture wars a distinctively Irish tone. The Irish-American editor of Salon, Andrew O’Hehir, once said: “When you think of the face of white rage in America, it belongs to a red-faced Irish dude on Fox News.”

Bannon mimics some of this belligerent Irish cosplay, but he is also a shrewd observer of what remains politically salient among the Irish in the US, at a time when they are commonly viewed as mainstream assimilated Americans. He has described the Trump movement as “people who punched out of the system and guys serving in the military, people who are the backbone of civil society in America, coaching little leagues, supporting the church, working-class Scotch-Irish in the South and blue-collar Irish Catholics in Pennsylvania, Iowa and Michigan.”

Bannon was instrumental in Trump’s outreach and appeal to what he calls “Hammerhead Micks”. In this sense, the Irish Trump already exists.

The romance and nostalgia in his comments on Irish Americans was echoed in a recent interview in the Financial Times: “There’s a natural Irish cussedness, a spirit of Molly Maguires [a 19th-century US secret society of Irish immigrants] that extends from Pennsylvania to Ireland ... They are invisible to Irish politics. We want to put the fear of God into Ireland’s political and media establishment.”

But while Bannon’s take on disaffected Americans of Irish descent has been politically effective, his views on Ireland seem comparatively naive. In this, he reflects a broader myopia in Irish America about the homeland.

Irish-American Partisanship

Romanticisation of Irish and Irish American history is a key element in the maintenance of Irish American identity today, shoring up very different political perspectives. On the one hand, there is the progressive story of how the Irish learned from the injustices they encountered and used this as the lodestone of a liberal politics of empathy. On the other hand is the reactionary nationalist story that takes its historical compass from a closed history of immigrant victimisation. This narrative distinguishes its descendants’ Americanness as authentic and earned. Today, these contesting histories clash over questions of white privilege, immigration and what it means to be American in the era of Trump.

This is evident in the responses I have been getting to research for a book on contemporary Irish America, which includes online surveys (with over 5,000 respondents to date) and interviews with Americans of Irish descent. The views of respondents are notably, though not surprisingly, coloured by the unsettling partisan politics and ethnonationalist discontents roiling the US today.

In these surveys and interviews, Ireland serves as something of a Rorschach test for Irish-American partisanship. Those on the left see it as a progressive liberal paradise – “the Irish sense of social justice is something we have lost here” – and a place many express a desire to move to. Meanwhile, those on the right view Ireland in more dystopian terms as woke, godless and under attack by immigrants: “Ireland is full. Please limit immigration into Ireland and preserve your culture.”

While the perspectives and language of both extremes are skewed, they are also significant as registers of the disconnections and misrecognitions between diaspora and homeland today, as Atlantic bonds wane.

Bannon’s sense of Irishness is clearly aligned with the dystopian, Maga view of Ireland, which laments its present realities while romancing the revolutionary past of the Old Country. It helps explain his promotion of Conor McGregor for the presidency of Ireland, an early indicator of his now explicit statement of intent of finding an Irish Trump.

In the survey I run, I ask respondents to name the Irish or Irish American person they most admire. The name McGregor only rarely appears; JFK is way out in front. Bannon’s ancestors would be proud.

This article was originally published in the Irish Times, 25 January 2026.