Picture This: How Life Magazine Framed America's Wars

This article is abstracted from a chapter by the author in the book Life Magazine and the Power of Photography, edited by Katherine A. Bussard and Kristen Gresh, published by Yale University Press. The book accompanies a current exhibition of the same title at the Princeton University Art Museum that runs until 21 June 2020

Larry Burrows, Reaching Out, Mutter Ridge, Nui Cay Tri, October 5, 1966.

Reflecting on Life’s World War II years, publisher Henry R. Luce observed: “Although we did not plan Life as a war magazine, it turned out that way.” This was less accidental than Luce suggests, for a good deal of Life’s editorial and creative energies went into its coverage of the lead-up to and duration of World War II and wars and international conflicts beyond 1945. To be sure, Life was not envisaged as a “war magazine” at its founding in 1936, but war and international conflict became ideal focal points of its worldview and helped secure its role as the most popular picture magazine in the United States.

Luce conceived of Life as a national mirror, though a corrective one, in which the United States would see “a clearer image of itself and a broader sense of common referents.” That democratic vision was also imperial and global in conception, as he famously articulated in his 1936 prospectus for the magazine:

“To see life; to see the world; to eyewitness great events; to watch the faces of the poor and the gestures of the proud; to see strange things—machines, armies, multitudes, shadows in the jungle and on the moon; . . . to see and take pleasure in seeing; to see and be amazed; to see and be instructed.”

This worldview combined the will “to see” with a geopolitical will to power, reflecting ideological perspectives in line with the US rise to globalism and its subsequent Cold War priorities. In the pages of Life the imperial American gaze is universalized and leavened via the democracy of its scope, the realism of its aesthetic, and the use of humanitarian frames and iconography. Adopting this vision, Life positioned itself as a champion of American exceptionalism and an interpreter of the United States’ new political role in global affairs.

Photography was key to this imperial perspective as it provided stimulating visual forays into a world opening up to American dominance and illustrated the sense of global wonderment expressed by Luce. War provided an especially rich visual terrain for a “new photojournalism” that would create dynamic, attention-grabbing images of conflict and suffering and provide candid close-ups of ordinary Americans at war.

This mission of seeing and instructing shaped Life’s coverage of international affairs from the build-up to a global war in the late 1930s to the ignominious US retreat from Vietnam in the early 1970s. Not that Luce’s ideological will was simply stamped on all of Life’s reporting on war; rather it influenced the prominent editorial guidelines even as it was often tested or resisted by writers and photographers.

WWII in Europe

Throughout the later 1930s Life frequently editorialized about global conflict and the build-up to war, reflecting Luce’s strong opinions as he eagerly joined the debate between interventionists and isolationists in the United States. Luce was keen to focus American public attention on international conflicts and shape opinion, and the magazine published gruesome pictures to attract that attention. In January 1938 it published a dual photo-essay that juxtaposed stories on the Spanish Civil War and the conflict between China and Japan, with an introductory statement that comments: “Dead men have indeed died in vain if live men refuse to look at them.” This would be a refrain of Life’s editorializing about global conflicts, at once a foil to American isolationism and public disinterest in international affairs and a moralizing claim to an act of witnessing that is aligned with Luce’s exhortation “to see and be instructed.”

In the later 1930s Life ran stories on German military belligerency and on the need for American readiness for war. It would sound a full-blown alarm following the German attack on Britain in late 1939, and this conflict became a key focus of the magazine’s coverage of the war leading up to the US entry. Luce wanted imagery that would galvanize American public opinion, and his US-based editors worked closely with the London-based photographers to ensure they produced material with a strong propagandistic impulse and effect. In late 1939 and throughout 1940 Life ran a number of photo-essays on “the Battle for Britain” and British defenses against German attack. Much of this was framed and editorialized to accentuate not only the plucky resistance of the British but also the need for the United States to protect shared values now under attack. The front cover of the September 23, 1940, issue, titled “Air Raid Victim,” shows a young English girl with a bandaged head in bed. Clutching a stuffed toy, she looks blankly straight at the camera. Much of the imagery emphasized the iconography of urban destruction, filtered through American perceptions of Britain. The text accompanying a photo-essay titled “Hitler Tries to Destroy London,” in the September 23, 1940, issue, reads, “Some of the world’s most famous picture-postcard scenes last week crumbled under bombs.”

D-Day, June 6, 1944, saw the start of Operation Overlord, which launched the invasion of western Europe by Allied forces, with one thousand warships delivering 175,000 troops to Normandy beaches in northern France. Robert Capa accompanied the Sixteenth Regiment of the First Infantry Division on the second assault wave. The attempted landing was chaotic due to harsh weather, ill-timed bombing supports, and the too early release of tanks and other materiel into deep water. Many troops were stranded in the water, and there was confusion as they floundered amid heavy German fire. It was this atmosphere of panic and paralysis that Capa captured in his photographs. Only eleven photographs of the landing taken by Capa have survived, and five of them were published in the June 19, 1944, issue of Life.

Robert Capa, “Beachheads of Normandy,” Life, June 19, 1944.

Capa’s pictures quickly became iconic images of World War II, though there are conflicting views as to why so few photographs survived and why they are so blurred. The conventional story told by Capa and many of his acolytes is that he took more than one hundred photographs but most of these were destroyed in Life’s London office in the effort to rush the prints. It is a story that has been challenged in recent years with charges that Capa had a panic attack on Omaha Beach and the salvaged negatives were all he shot on the landing and there was no post-exposure damage to them during processing. There is no doubting the authenticity of the surviving photographs though, and whatever the cause of their grainy and blurred effects, these have heightened their surreal quality.

Stories of concentration camps and the mass murder of Jews in Europe had circulated for many months before becoming a major news story in the United States in April 1945. In a harrowing gallery of images titled “Atrocities,” published in Life on May 7, 1945, both the intimacies and the scale of suffering and death were represented, from dying inmates at Belsen, to the haunting looks of emaciated prisoners in barracks at Buchenwald, to piles of barely distinguishable charred corpses at Gardelegen, to the “bodies of almost 3,000 slave laborers” laid out along a street in readiness for burial at Nordhausen.

Life photographers would later write or speak of their experiences at these sites, finding it difficult to articulate scenes that defied comprehension and that called into question their roles as photographers. George Rodger acknowledged being traumatized by what he had seen and developed guilt about taking photographs of the horrors: “I determined never ever to photograph war again. . . . If I had my time again, I wouldn’t do war photography.”

George Rodger, Young Boy Walks Past Corpses, Bergen-Belsen, Germany, April 20, 1945

The text accompanying the photographs in “Atrocities” states, “They are printed for the reason stated seven years ago when, in publishing early pictures of war’s death and destruction in Spain and China, Life stated, ‘Dead men have indeed died in vain if live men refuse to look at them.’” This is a powerful reassertion of Luce’s injunction to see and learn but it also elides the significance of what is being visualized (and at no point makes reference to the Jewish identity of the majority of the dead). More than any other visual documentation of war’s horrors, the imagery of the Holocaust recast the status of documentary photography, the visual horrors becoming a benchmark of human destructiveness and a symbolic limit point of the humanistic imagination.

World War II in the Pacific

The US entry into the war excited Luce, and he ensured that his magazines took the lead in reporting on the Pacific war, running major stories on it and sending leading journalists and photographers there while other news services were more preoccupied with the European theater. Luce’s orientalism was reflected in much of the coverage, which signaled the alterity of foreign places, peoples, and climates more acutely than did the coverage of the European war and included more overtly racist representation of the enemy and its dead.

In 1943 US media personnel arrived in large numbers to follow the fights for islands as the Japanese were pushed back to their mainland. Life provided extensive photographic coverage: Ralph Morse shot the battle for Guadalcanal, Peter Stackpole covered Saipan, George Strock photographed the battles for New Guinea, and John Florea photographed the battle for Tarawa. David Douglas Duncan, who enlisted in the US Marine Corps, flew several combat missions and recorded the marines’ aerial activities.

Heavy censorship of the Pacific campaigns by the US military ensured no images of dead American soldiers appeared in American media. Life chafed at the restrictions, making editorial and more direct appeals to the government to lift them. As the Department of War and President Roosevelt’s advisers became concerned about potential home-front complacency about the war, the decision was made to release more graphic images, including of dead soldiers. On September 20, 1943, Life published a photograph by George Strock of three dead American soldiers lying on a beach at Buna.

George Strock, Buna Beach, New Guinea, 1943.

The full-page image, captioned “Three Dead Americans on the Beach at Buna,” was accompanied by a full-page editorial that made the case for publication: “here on the beach is America, three parts of a hundred and thirty million parts, three fragments of that life we call American life: three units of freedom.” Government surveys taken after the Buna Beach picture’s publication showed that Americans increasingly supported the appearance of graphic imagery.

In 1944 the magazine sent the renowned photographer W. Eugene Smith to the Pacific theatre where he would cover thirteen landings until he was severely wounded on Okinawa in May 1945. Smith’s photographs of the battles for Saipan and Iwo Jima are celebrated as among the very best examples of war photography. Smith was a pacifist, drawn to the human tragedy of the conflict, which he depicted with evident compassion and which fired him to produce graphic depictions of the inhumanity of war and to express greater sensitivity about racial issues than most of his colleagues.

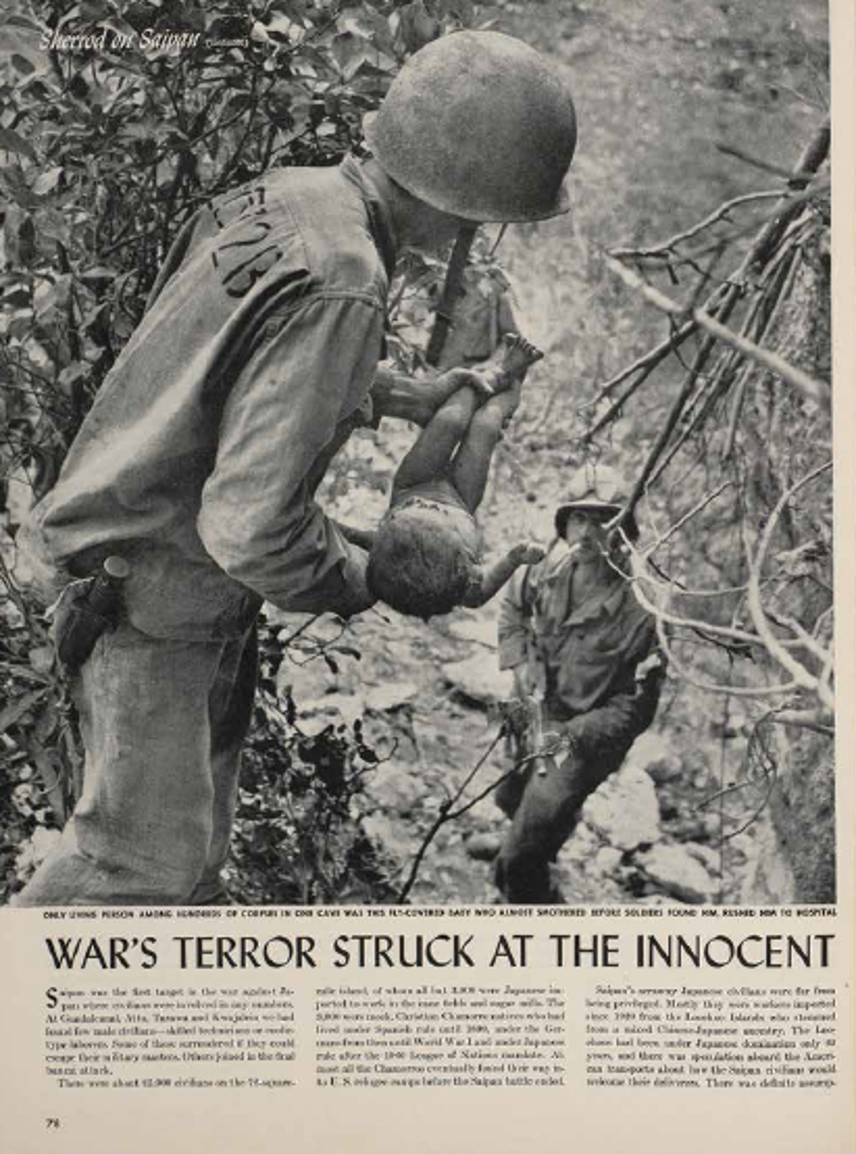

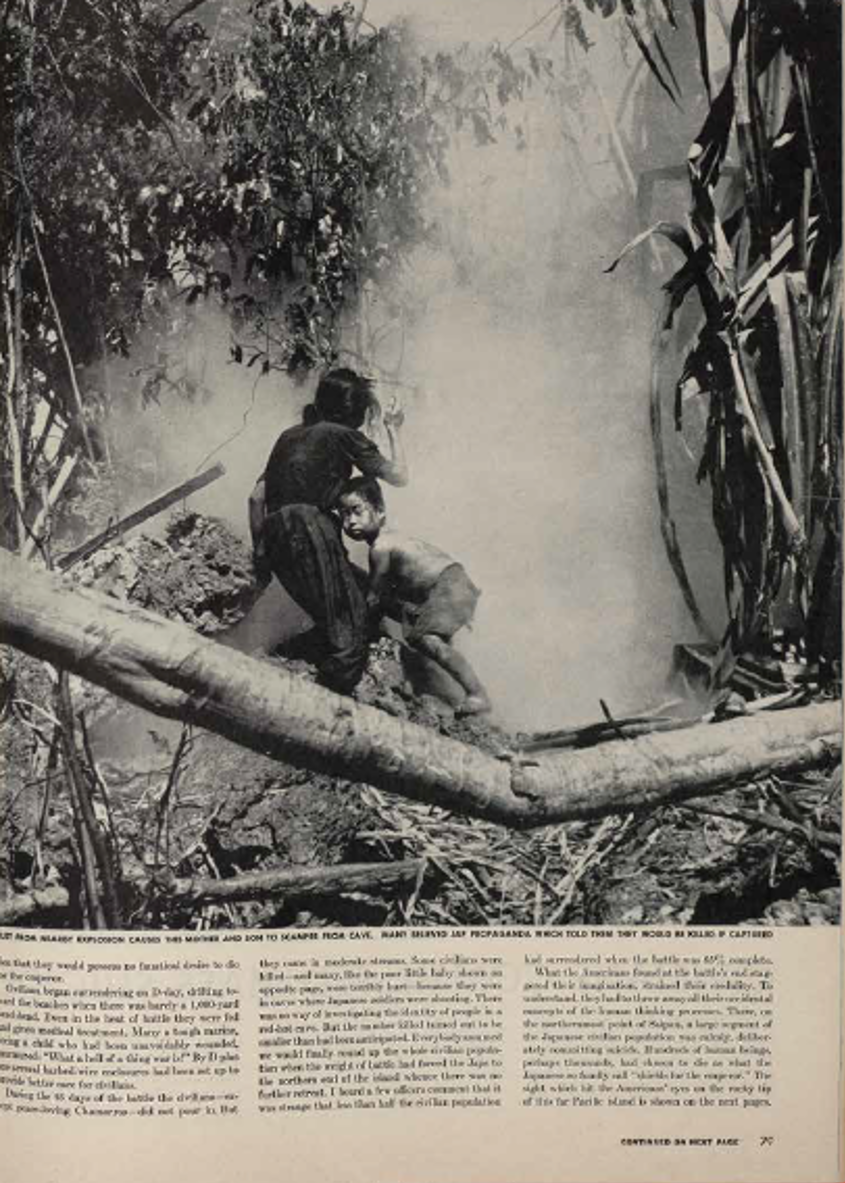

Smith’s first major assignment was to cover the invasion of Saipan, in the Mariana Islands, in June 1944, the focus of a huge American naval force as it pushed toward Japan. Although he was not present to photograph the US landing on the island, he pictured the aftermath, including graphic scenes of death and destruction but also moving scenes of civilians, most of them terrified and in hiding from US troops, some committing suicide. As civilians were found, often smoked out of caves, Smith took sympathetic shots of the scared and disheveled. Two of the images taken as the soldiers searched caves are juxtaposed to powerful effect in Life’s layout. On the left is a marine carefully holding a dying infant found in a cave, one of Smith’s most famous photographs; on the right is a woman and child just emerged from a smoking cave, bewildered and vulnerable. With the images set side by side for the reader in this way, it is impossible not to notice commonalities, not least due to the echoing compositions: the arc of the soldier’s body and the infant’s head in one mimicked by the broken tree in the other, and the pietà connotations hovering in the background. Together, they underline the humanism of Smith’s vision.

W. Eugene Smith, “Saipan,” Life, August 28, 1944

On August 20, 1945, Life published photographs of a new type of warfare never before seen by an American public: the clouds caused by the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Photographs of the “mushroom clouds” billowing twenty thousand feet above each city were printed on opposing pages in the layout. The images, taken by military sources, became immediately iconic, inspiring awe and portending a fearful future. They inaugurated the visual culture of the “atomic sublime,” and the reproduction of similar imagery throughout the early Cold War would signify both military and technological progress and impending catastrophe. As with the images of the Holocaust Life had published a few months earlier, the photographs of the atomic bombings signaled the limits of visual representation and challenged the surety of the American worldview.

Korean War

Well before World War II ended, Luce was preparing his media empire for a postwar future that would see his ideas of the “American Century” realized in US global leadership. The outbreak of conflicts in Korea and Vietnam excited Luce’s orientalist perspective as fresh opportunities to destroy the Communist regime in China, but these were wars of a new kind and the manufacture of national consensus would prove more elusive.

The “police action” known as the Korean War attracted great media interest in the first months of the conflict; by August 1950 there were 163 accredited American press representatives in Korea. Life photographers covered all major phases and accessible environments of the conflict. Most of the Western journalists were stationed in Tokyo, making frequent visits to the front, their movements and transmissions aided by US military, including free use of its communication systems. It was possible to send photographs by wire from Korea to Tokyo within a few hours. David Douglas Duncan for the most part covered the movements of US Marines, including the recapturing of Seoul and the retreat from Changjin, and became the first photographer to fly in a military jet on a combat mission. Carl Mydans covered the Inchon landing by marines in September 1950and documented the US Army’s First Cavalry Division’s landing in P’ohang-dong. Margaret Bourke-White focused on Korean civilians and the guerrilla warfare conducted by South Korean forces. Werner Bischoff photographed inside prison camps in Koje.

Uncertain American framing of the Korean conflict was compounded with China’s entry and the resulting defeats for US and United Nations forces in freezing weather conditions at the end of 1950. On December 25, 1950, Life published a photo-essay by Duncan who accompanied a column of marines as they retreated from the Changjin Reservoir. The essay, titled “There Was a Christmas,” had a significant impact in the United States. The photographs illustrate the harrowing conditions of the retreat and also record the innate heroism of the suffering men. The published layout is a classic example of the photo-essay genre that Life had perfected, following a narrative arc that draws the viewer into the experience depicted by focusing on its human essence, in this instance the suffering and eventual survival of the men. The first image in the sequence is of an individual marine holding a can of frozen beans and staring into the sky. The retreat takes on allegorical significance in the images, an American tragedy that unfolds as a redemptive exodus, and it resonated with Life’s readers.

David Douglas Duncan, Soldiers Pass the Bodies of Men Killed during the Retreat from the Chosin Reservoir, North Korea, December 1950

On August 3, 1953, shortly before the truce was signed, Life published a portentous photo-essay by Duncan titled “The Year of the Snake.” Accompanied by his own text, it reviews conflicts and instability in Indochina and presents the French cause unsympathetically, showing lazing French officers and an army made up mostly of foreign mercenaries. When Duncan’s report appeared in Life, it annoyed the US State Department and enraged Luce, who accused him of having an “emotional attitude towards the French” and placed him on the “inactive list.” The fallout between the publisher and his star photographer may have involved clashing egos but also indicated the lack of a coherent narrative in Life about the wars in Southeast Asia and about what the American public was being asked to see there.

Vietnam War

In its coverage of the war in Vietnam, Life sought, as it had with World War II and Korea, to reflect the nation’s challenges and provide coherent and cohesive narratives about relations between domestic and foreign affairs. The nation, however, in the sense of an imagined community with broadly shared ideals and values, was unraveling during the 1960s, with dissent and protest at home, and it was becoming less clear what constituted an American worldview in actions abroad. Life’s editors struggled with whether or not to reflect increasing public disaffection with the war, with management resisting until after 1968, when the tide of American public opinion clearly turned.

Life was well served by its photographers during the Vietnam War. Several were innovative, especially in their use of color, which Life strongly promoted as it sought to distinguish its product from that of television. Larry Burrows photographed the war from 1962 until his death in Laos in 1971, and his work constitutes a remarkable documentary chronicle of the conflict and an influential template for future photojournalistic treatments of the United States at war. Co Rentmeester, a young Dutch photographer who became a staffer in 1966, was as adventurous as Burrows in experimenting with form, color, and new technologies. John Olson secured a job as staff photographer with Life with his photographs from the bloody battle of Hue in 1968 in the midst of the Tet Offensive. In the early 1970s he photographed lead stories on returning vets and the impact of war on American communities. David Douglas Duncan sought and was granted assignments to photograph American marines at battles in Con Thien and Khe Sanh in 1967 and 1968.

Larry Burrows, Reaching Out, Mutter Ridge, Nui Cay Tri, October 5, 1966.

Burrows’ first major Vietnam War story, published in Life on January 25, 1963, was exceptional, presenting the first extended color imagery of the war in a major magazine. In autumn 1966 he covered a marine battalion’s struggle to take hills from entrenched Vietcong forces in the demilitarized zone. Burrows’s images focus on wounded marines, including an injured gunnery sergeant being helped to an evacuation point. Another photograph he took of the same man was not published at the time but would become iconic when Life published it in 1971.

It depicts an injured soldier at center reaching toward a wounded marine, who lies sprawled before him. The sprawled man, covered in mud and bandaged on both legs, is propped against a tree stump, his left arm cast toward the viewer, gripping another tree stump. They are surrounded by several soldiers and the muddy landscape of the hill, with the lush jungle hills in the far background. The tableau-like effect of the image is powerful, conjuring symbolic references that transcend the immediacy of the scene, including racial difference. By 1971 the photograph could be viewed afresh and took on renewed significance in relation to the broader disillusionment about the war shared by the American media and public.

In the early years of the war Life presented a positive view of the American presence in Vietnam through coverage that accentuated humanitarian intentions and activities, though this framing would shift to reflect doubts about American prosecution of the war. In early 1965 the photographer Paul Schutzer spent six weeks with US marines in South Vietnam, and Life published a twenty-two-page photo-essay that documented the mission, with particular focus on efforts to win the hearts and minds of the Vietnamese. In 1967 Co Rentmeester photographed the activities of a combined action platoon of American and Vietnamese troops engaging Vietnamese villagers as part of the “pacification campaign,” with close focus on American soldiers befriending a crippled child they call Louie. This focus on wounded Vietnamese children would become a common trope in later Vietnam stories published by Life. The sympathetic framing in such stories renders a tension that appears in much of Life’s coverage of the war, between the humanitarian and imperial aims of the American mission. The dialectics of care and domination in the images emblematize the contradictions of the American mission in Vietnam and render the limits of “compassionate” image-making in its representations.

The Tet Offensive of 1968 fueled disillusionment with the war in the United States, and as the daily “body count” of US soldiers rose steadily, questions about the value of pursuing war became more commonplace in the media. On June 27, 1969, Life published a gallery of photographs of US soldiers killed in Vietnam during one week under the title “The Faces of the American Dead in Vietnam: One Week’s Toll”.

Spread from “Vietnam: One Week’s Dead, May 28–June 1969,” Life, June 27, 1969

The 217 images, published in the format of studio portraits, were made up of high school photographs, graduation shots, and formal military pictures, most of them provided by the families of the deceased. The images were shocking due to both their intimacy and aggregation, and their publication had visceral resonance with the public, occasioning more than thirteen hundred letters and broader media discussion. Absent the immediate context of war, the faces of the young men stared out at viewers with an implied innocence that belied their fates. The editorial is brief and low-key, stating, “It is not the intention of this article to speak for the dead,” and there is minimal attendant text; the simplicity and directness of the production, all in black-and-white, was its own message. It is an alternative form of war photography that dials down on heroism and uses photographs to reconnect the public with what they were refusing to look at.

The publication of “The Faces of the American Dead” signaled a marked editorial shift away from support for the war, though this had been under way for a few years. Luce had stepped down as editor in chief of all his publications in 1964, yet he maintained a strong interest in the magazine and remained a belligerent supporter of US involvement in Vietnam until his death in 1967. It is doubtful that he would have sanctioned publication of “The Faces of the American Dead.” To be sure, the images might be viewed as coherent with Life’s history as a “war magazine” in its commitment to represent the violence and death of conflict. The 1938 editorial that concluded “Dead men have indeed died in vain if live men refuse to look at them” has uncanny resonance in the 1969 gallery of American dead in Vietnam. Where that visual challenge was originally published to press a nation toward intervention in foreign conflicts, these later images were published to ask Americans to take stock of the costs of war.

* * *

During most of the Vietnam War Life had a weekly print run of eight million copies, but by 1970 the magazine was in financial trouble, and it closed as a weekly magazine in December 1972. While the closure was occasioned by financial necessity, with falling advertising revenues due to the competition of television and the rising costs of publishing in color, it also reflected the magazine’s fading relevance as a national barometer and mirror. An increasingly divided American public no longer saw itself reflected in the pages of Life, and the magazine could not visually suture the divisions in the American worldview. In many ways its visual coverage of the US at war provided its most compelling examples of Luce’s imperial vision and his founding injunctions “to see and be instructed,” but it also revealed the limits of that vision, exceeding its editorial and ideological frameworks.